What follows is a long-form essay about the recent evolution of western alienation and populism on the American plains and Canadian prairies. For those who want the brass tacks, here’s a summary:

Within the span of a generation, the West’s identity has shifted from one of limitless opportunity to one of sobering boundaries. Declining resource access and changing social norms have some Westerners feeling held back and left behind. In response, right-wing leaders have crafted a new populism rooted in cultural loss and exclusion. The region now faces a choice: adapt to new realities or double down on its past. We need new leadership that’s focused on building a common future beyond this polarization.

The Limitless West

Re-watching Ken Burns’s epic docuseries got me thinking about how our vision of the West has shifted lately.

In one particular episode, Burns recounts how Bismarck, North Dakota’s founders built the state capital about a mile outside town, expecting the city to grow around it. This decision reflected their belief in Bismarck’s bright future as a regional center of commerce and government.

Legend has it, the same hubris convinced Albertans to build the Edmonton International Airport about 30 kilometers south of downtown.

Such decisions captured the mood of the region: too big for its britches.

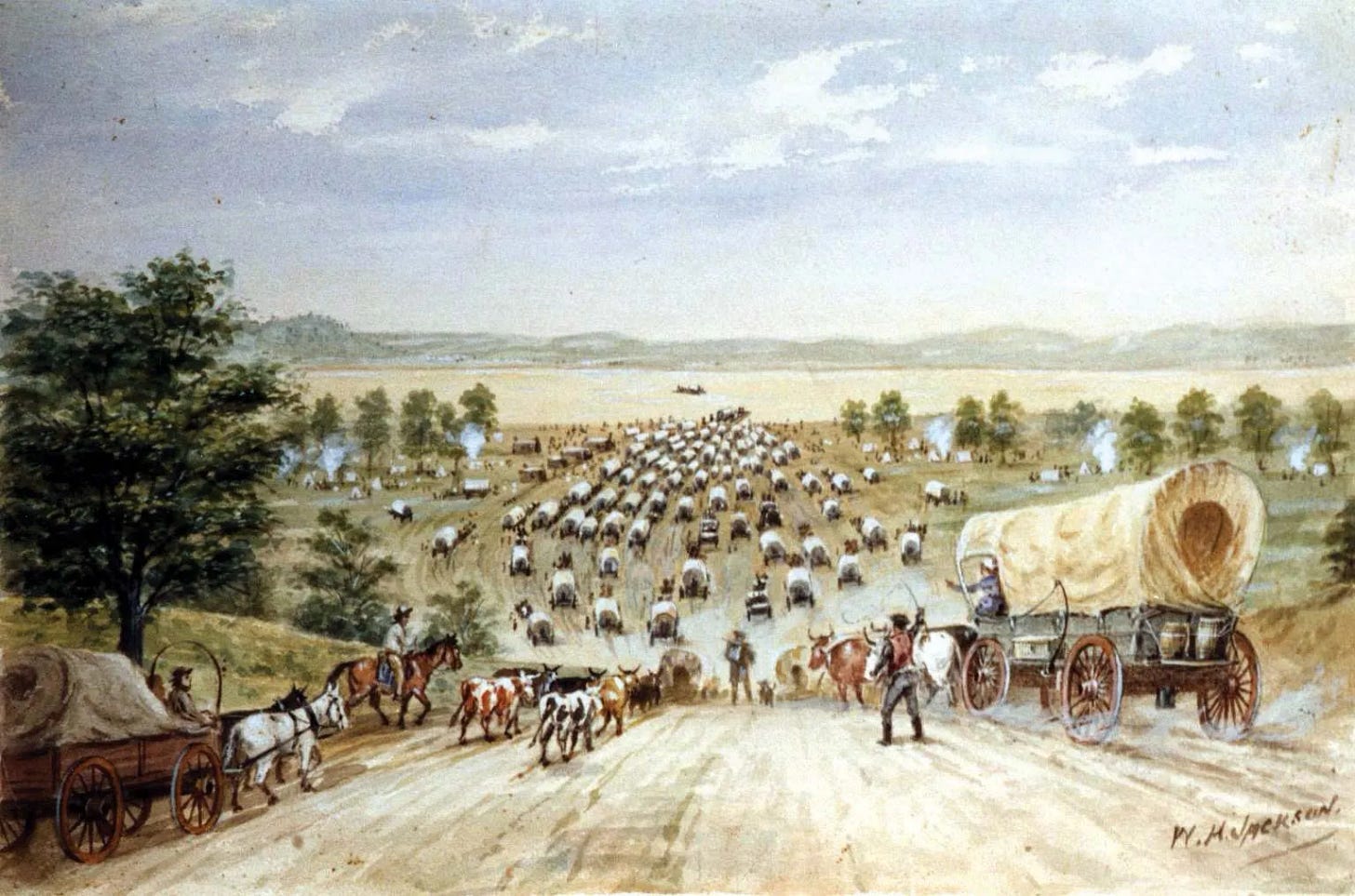

For generations, the mythology of the North American West has been one of boundless horizons. Depicted in movies and television shows, the West has always been a place where hard work and self-reliance could yield prosperity, where resources seemed limitless, and where individuals could live unencumbered by external constraints. It was the land of pioneers, of boomtowns, and of unfettered ambition.

But for this latest generation, the West is no longer a frontier. For some, it has become a place of boundaries. Or at least it feels that way. And those feelings are having a major effect on the collective psyche and politics of the region.

Feeling Fenced In

The dominant story of the West has largely revolved around economic opportunity tied to natural resources. Whether it was wheat in Saskatchewan, oil in Alberta, coal in Wyoming, gold in California, or timber in British Columbia, prosperity was found in the land. Today, these resources remain, but the ability to access them seems constrained by economics and politics.

Global shifts toward renewable energy, automation, international climate agreements, and domestic policies on carbon pricing have all altered the economic ambitions of the region. It is not just that jobs in oil and gas are disappearing; it is that these industries, once central to Western identity, are now treated as political and environmental liabilities by the rest of the world.

For some Westerners, this is more than an economic transition. It amounts to a loss of status. The industries that built the West are no longer seen as the backbone of our economic future nor as honourable professions, but as relics of the past and “part of the problem.” To them, the world is moving in directions other than westward, and they feel like they are being left behind.

These sentiments need not be grounded in economic reality to have an impact on the political culture. Oil and gas is enjoying record production numbers in Alberta, for example, although the number of people directly benefiting from that wealth is not keeping pace. To point this out to the aggrieved is only to feed their sense of persecution. It doesn’t feel like people like us are doing well. Something feels wrong.

It wasn’t always this way. Yes, westerners have often felt held back from reaching their full potential. Alienation is part of the political culture of the region. But now they’re sensing something different: it’s as if they’re falling behind.

This sentiment is more than just economic.

Across Canada and the United States, social norms have shifted — at least somewhat — in favor of collective responsibility over individual autonomy. Diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) policies, environmental regulations, and public health measures have introduced new expectations in workplaces, schools, and elsewhere. While vocal minorities have resisted, mainstream public opinion has been supportive of these measures.

The Wild West notion that one should be free to speak and act without external constraints is now met with counterarguments about the responsibilities that come with that freedom.

For some, this represents necessary progress toward a more just, inclusive, and sustainable society.

For others, it feels like an erosion of the West’s core values. To them, the unchecked independence that once defined the region is now hemmed in by social expectations being imposed by urban elites, particularly in “the East.”

The ensuing thinking goes something like this: if “they” want to fence us in, we’ll go one better and build a firewall around our region to keep “them” out.

In Canada, populist leaders rail against the “woke Laurentian establishment” in Toronto, Ottawa, and Montreal the way American Westerners howl at Washington, DC. The juxtapositon of West versus East is intentional. There would not be an “us” without a “them”.

A Myth Built on Erasure

Of course, the idea of the West as an unclaimed, unbounded frontier was never true. It was a myth built on the attempted erasure of Indigenous peoples and the violent dispossession of their lands. The “limitless” expansion that fueled Western prosperity (“manifest destiny”) was only possible because governments, settlers, and industries operated within a framework of settler colonialism, treating Indigenous presence as an obstacle to be eliminated.

In this sense, the full story of the West was not just about resource extraction. It was about asserting a particular kind of identity that positioned white settlers as the rightful inheritors of the land. Government policies actively recruited Western European immigrants while restricting or outright denying land access to Indigenous peoples, creating a racialized hierarchy that defines who “belongs” in the West that survives to this day.

The mythology of the frontier was built on stories of hardy pioneers taming a wild land, but those stories conveniently left out the Indigenous peoples who had lived on and cared for these lands for millennia. It also sidelined the contributions of racialized settlers.

Reconciliation and anti-systemic racism initiatives are challenging these long-held narratives. Indigenous communities across the West continue to assert land rights, reclaim cultural traditions, and demand recognition of historical injustices. Court rulings, such as those affirming Indigenous land title, and policy shifts toward Indigenous self-governance are slowly dismantling the colonial mindset. The idea that the land is simply there for the taking is not universal, and for some in the West, this is an uncomfortable reckoning.

Many Westerners see this shift as a necessary correction to history and an important step toward reconciliation. Others view it as an erosion of the identity they were raised with. By highlighting their ancestors’ past wrongdoings and ongoing colonialism, it presents a challenge to the very idea of what it means to honourable. A sense of alienation long felt by Indigenous people and racialized settlers is now being felt by the white settlers, albeit in very, very different ways.

Falling Behind: Psychological Angst

The feeling that the West is being left behind is not just economic and cultural. lt is socio-psychological. It is tied to relative deprivation, the sense that one's region, one's community, or even one's own life is failing to meet the expectations set by oneself and previous generations.

In the West, many people were raised with the expectation that they would be better off than their parents. Homeownership, stable careers, and financial security were seen as natural outcomes of hard work. Today, those assumptions of “prosperity doctrine” are threatened. The rising cost of living, stagnant wages, volatile commodity markets, and uncertainty about the future have eroded confidence in the idea that each generation will surpass the last.

This is not just a Western Canadian phenomenon, of course. The decline of fisheries in Atlantic Canada comes to mind. As does the economic malaise of America’s Rust Belt and Coal Country, where deindustrialization and the green shift left entire communities struggling to adapt.

In these regions, economic decline is intertwined with cultural identity. The industries that once defined these places were more than just economic drivers; they were symbols of a way of life. Their decline is not just a loss of income but a loss of meaning — one felt by more than just those who lost their livelihoods.

The angst is not theirs alone. People from all parts of North America are struggling with precarity and challenges with unaffordability. This is a confusing and disorienting time for most people. Westerners are not exceptional, though many may feel themselves to be.

Indeed, sentiments of “falling behind” are strongest among those who see the West as not just a region but almost as a nation. Drawing from our Common Ground research, there is evidence that these feelings are more pronounced among those who identify strongly with the idea of Western exceptionalism. They see their provinces and “the West” as culturally distinct, unfairly maligned, and excluded from national decision-making.

Superiority is an important part of that exceptionalism. For generations, Westerners have seen themselves as ahead of the pack, as fueling the economic engine of their countries, and as representing their nation’s political heartland. Today, some Westerners bristle at being considered ‘fly-over country’ or at seeing other regions rise in prestige relative to their own.

In this sense, the West’s greatest challenge may not be economic or cultural decline, but the fact that some people were conditioned to believe in both limitless opportunity and superiority. The mythology of the West promised a permanent frontier. But frontiers, by definition, do not last forever. Like other regions, the reality of the modern West is now one of boundaries—economic, cultural, and political.

For some, these boundaries represent progress, a necessary evolution toward a more sustainable and inclusive society. Like their agrarian forebears discussed below, these progressives want to move forward.

For others, the changes represent a loss, a closing off of opportunities that once seemed infinite. They want to turn backward to reclaim circumstances when they felt honoured instead of feeling maligned. Enter the new brand of populism that has gripped communities across the West.

A New Form of Populism

To be clear: this is not the populism of agrarian protest that once defined the region. That earlier movement united religious folks, farmers, workers, and small business owners against churches, corporate monopolies, banks, and distant governments that controlled their lives. Through protests, cooperative movements, and unions, Westerners sought to democratize power and expand economic opportunity for people like them. Unlike today’s exclusionary populism, which defines “the people” by who doesn’t belong, this earlier wave was about challenging concentrated power to benefit all who labored.

Of course, the cultural make-up of the West was different back then. And there was still discrimination, whether aimed at women, gender minorities, disabled people, Indigenous or racialized people, Eastern European immigrants, and others. The Ku Klux Klan had a foothold, for instance, and the insular sects of some churches bred exclusion of all kinds.

In this sense, the idea of “belonging” in the West has always been selective. It has excluded, sometimes violently, those who did not fit into the vision of what it meant to be “from here.”

Yet, the agrarian populism was largely a bridging form of social capital expansion, one aiming at a shared form of prosperity and optimism for the future.

By contrast, today’s populism is fueled by a sense of decline, resentment, retrogression, and exclusion.

This new form of populism is animated by the belief that the West is not only being left out and held back, but deliberately undermined by distant elites who do not share its values. It borders on conspiratorial, at times.

This is a populism of loss, rooted in the idea that the West was once great, that its people were once free to shape their own destiny, and that both of these things are no longer true. The message of modern populists is clear: the West can only be great again if it restores the narrower definition of who counts as a valued member of the community.

Today’s populist movements look backward in order to tap into these old hierarchies, even if implicitly. When they speak of “taking back” Western identity, they mean restoring the dominance of a particular cultural order — one where traditional industries like oil, gas, and agriculture are unchallenged, where the rights of business owners trump those of workers, where parental authority overrides childrens rights, and where social and political norms preserved the status of the traditionally privileged.

This is why contemporary populists rail against not only Ottawa or Washington but also against DEI initiatives and reconciliation efforts. These are not just policy disputes; they are seen as existential threats to the identity of the West itself.

If the West is a place where “real” people (men) drive trucks and real work requires showering at the end of the day (instead of the beginning), then anything that challenges that ideal is cast as an attack on Western heritage, whether it be the rise of knowledge-based economies, urbanization, social justice, or demographic change.

Belonging in the West

In these ways, the West’s new populism is not just about who holds power but about who belongs. The anxieties fueling western alienation today are often articulated in economic terms: the decline of resource jobs, attacks on natural resource industries, the erosion of rural infrastructure.

But beneath those economic concerns lie deeper fears: that the West’s best days may be behind it. And that some Westerners, as they have imagined themselves, are becoming what Arlie Hochschild referred to as Strangers in their Own Land.

This sense of alienation is not unique to Western Canada or the American interior. It echoes the Brexit-era laments of a “lost England,” the MAGA movement’s yearning for an older, whiter America, and the nationalist retrenchment seen in parts of Europe.

In the West as elsewhere, populist leaders tap into a potent mix of economic nostalgia and cultural grievance, offering a simple explanation for complex problems: The world changed, and it wasn’t your fault. It was stolen from you, and only “we” can get it back.

Resisting vs Reimagining?

The core challenge for the modern West is not whether it can resist these changes (they’re happening), but whether it can reimagine itself in a way that does not rely on exclusion or building firewalls around the region.

The populist temptation is to double down on a shrinking identity, making their world smaller. Its impulse is to cast those who advocate for Indigenous sovereignty, climate action, or multiculturalism as enemies of the West rather than as part of its future.

But that approach can only lead to deeper divisions and greater precarity in a region that is increasingly reliant on people, partners, and ideas from the outside.

The same goes for folks on the other side. Actively marginalizing those who feel left behind will only deepen their resolve.

Many observers worry that how the West adapts to these new realities will shape its political and economic future. Will it find new frontiers in technology, sustainability, and innovation? Or will it cling to a fading past, resisting the changes that are already underway?

The first step involves recognizing the false dichotomy between nostalgia and the status quo — or at least the futility in that framing.

Breaking free of this black-and-white fallacy starts with shifting the conversation from a battle over the past and the present to building a shared vision for the future. Instead of seeing change as either an unmitigated threat or a boon, Western communities can treat it as a reality they must confront together.

This means investing in new industries while valuing the contributions of resource workers, embracing Indigenous and settler leadership, and fostering economic policies that ensure prosperity is widely shared.

It also means moving beyond the tired West versus East dichotomy. The challenges facing Westerners are not unfamiliar to people in other parts of the country, and vice versa. Whether through commiseration or learning, it’s important to build bridges with these other communities, instead of firewalls around the region.

The challenge is to channel Western values of resilience and optimism into adaptation, rather than retrenchment or replacement. The real test is whether Western communities can harness their pioneering spirit to create a future that is both prosperous and inclusive.

To recapture its imagination, the West needs to think bigger again. It needs leaders whose visions stretch beyond our current limits, to build dreams miles out of town in the expectation that we’ll all grow together in that direction.

good column. However, I think you also need to address the self inflicted identity challenges fostered by the Provincial governments. For example the west helped Harper to power. what did he do. He eliminated the grain board cooperative that supported farmers. now we have 70 - 90% of the grain trade in the hands of 4 American companies. do you think they give a damn about Canadian farmers? they are monopolists. in the grabbing of profits they are helping destroy the family farms. no wonder farm families are upset. The laws about foreign ownership also make for these huge corporate farms.

another example, the oil industry is controlled by big oil. again not Canadian but corporate monopolies. they have bought the governments to lower royalties, permit abandonment of their wells when sucked dry leaving the taxpayers to foot the pollution bill of decommissioning and going easy on pollution. the jobs the government thinks it is protecting will disappear when the companies can no longer make their huge profits. do you think they give a damn about Canadian workers?

my point is we have worshipped at the altar of "the free market"; which it isn't, and sold out our identity and economic independence to foreign monopolies.

I could go on. your point about the results of a dysfunctional myth of a golden past is right on, but solutions also need to be invoked to refind Canadian traditions and instruments that protected the population and its economic base.

Great article. Perhaps our pioneering spirit only flourishes when things are pre-ordained to go our way. My grandmother said “change with the times or get left behind.” The West has conveniently forgot about the cultures and lives that were decimated by colonization, the policies and systems of which continue to this day. No one likes to lose power or status. Suck it up. There’re new faces at the table. There might be a new table. This idea of eternal growth is at best, naive, and at worst, greedy. Evolve or perish. Share the wealth, and consider your great privilege to complain about the evolution of easy times. Indigenous People and racialized people have never known of these good times ‘we‘ lament are changing.

Looking backwards is not the way we will all thrive, and ensure the planet thrives with us. For without a stable ecosystem, the worries of today will seem minor. Water and crop disruptions, wildfire expansion, and vector-borne disease are but a few of the ways the ‘west’ will be lost. I already don’t recognize the province of my birth, and my health will be less robust than my grandmothers because of it.

There’s a bright future for all of us if we stop lamenting the inevitability of change. But the future belongs to all of us, not just those deemed worthy by an angry minority scrambling for the spotlight.